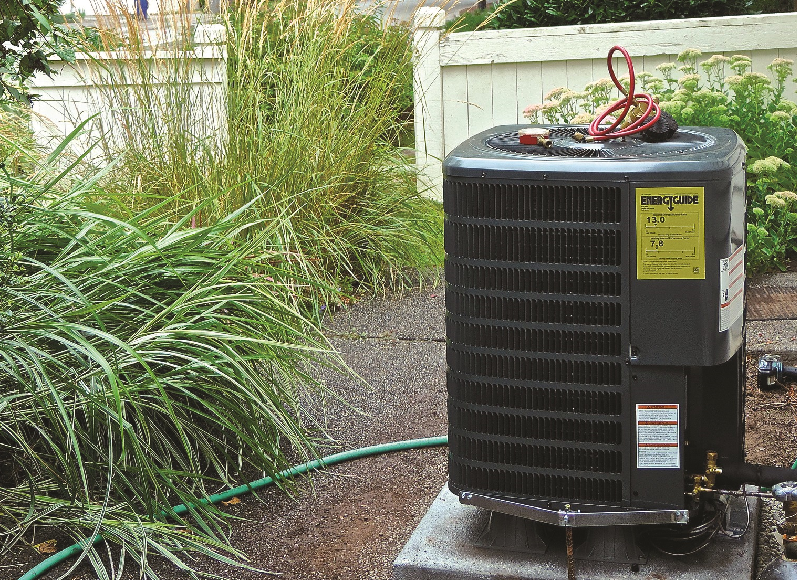

David Dietman was familiar with air source heat pumps (ASHPs) prior to installing one in his 1,470-square-foot hobby building in Clearwater, Minnesota. Positive experiences with heat pumps at his homes in Arizona and Florida encouraged him to try the technology in a colder climate.

ASHPs provide both efficient heating and cooling for year-round comfort. When properly installed, they can deliver up to three times more heat energy to a home than the electrical energy it consumes. This is possible because a heat pump moves heat rather than converting it from a fuel like combustion heating systems do.

Efficiency and environmental sustainability were top of mind when Dietman, a member of Stearns Electric Association, chose a centrally ducted model to cool his hobby building in the summer and provide heating to offset his high-efficiency propane furnace in the winter. His co-op also provided a $650 rebate for the purchase of this appliance.

“We try to be as efficient as possible and as nice to the environment as possible,” Dietman said.

ASHPs are an inherently efficient technology, resulting in a significant reduction of carbon dioxide emissions compared to traditional heating sources. And because electricity is increasingly generated by more renewable options — such as wind and solar — homeowners will further reduce their carbon emissions over time. Great River Energy is currently transitioning its energy mix from one that was heavily reliant on coal to a portfolio that will be over half renewable energy by 2025, making the ASHP heating and cooling Dietman’s space even cleaner.

Heat pumps provide consumers with 100% of a home’s heating needs down to temperatures as low as zero degrees Fahrenheit, or roughly 90% of all heating hours in Minnesota. The heat pump installed in Dietman’s hobby building supplies heat down to 30 degrees Fahrenheit, at which point the propane furnace switches on.

While he is satisfied with the setup, Dietman recommends that homeowners consider cold-climate heat pumps when purchasing a new heating system. A project recently conducted by the Center for Energy and Environment found that the efficiency of the newest generation of cold-climate ASHPS can operate down to minus 13 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Go with sub-zero,” Dietman said. “I would have installed [one] if I knew about it earlier — one that functions in the lowest temperatures. Get the best efficiency possible because it will save you money in the long term.”

" data-object-fit="cover">

" data-object-fit="cover">

" data-object-fit="cover">

" data-object-fit="cover">